David Thiry is the founder of R2 Mechanics, a developer and systems architect focused on offline‑first, privacy‑driven solutions for archives, museums, and research institutions. With a background in building high‑performance, autonomous computing systems, he works at the intersection of technology, ethics, and cultural preservation. This article reflects his vision of transforming transcription from a static service into resilient cultural infrastructure.

Published on: July 28, 2025

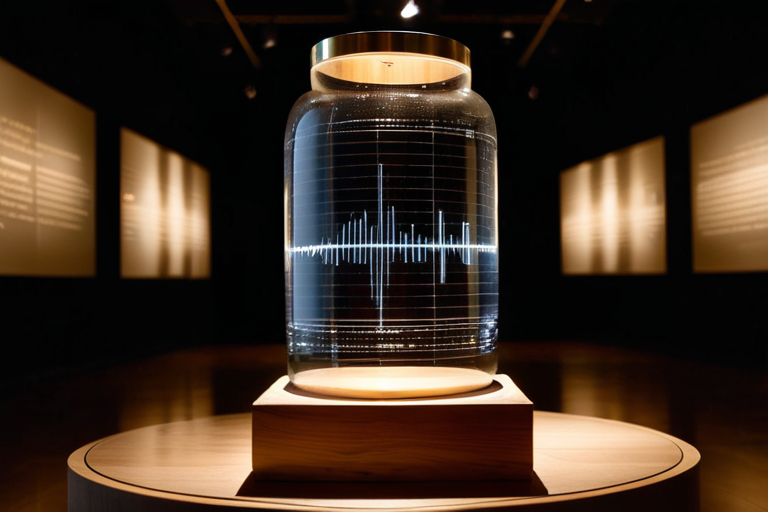

In a world that moves faster every day, memory is often the first thing to fade. Whether it’s oral history interviews, indigenous knowledge, audio diaries, or witness accounts—countless cultural voices exist only in fragile, analog form. Many are recorded on magnetic tapes, cassettes, or early digital formats whose lifespan is coming to an end. As time passes, background noise increases, tape reels degrade, and the original context of the conversations is lost. Yet these voices hold immeasurable value. They are repositories of knowledge, emotion, and identity—often the only record of communities whose stories were never written down.

Modern transcription technologies, especially those powered by artificial intelligence, offer a new way of preserving these voices. But it’s not just about converting spoken words into text. True transcription is an act of listening—of carefully interpreting, contextualizing, and preserving the integrity of the original message. It requires not only computing power but sensitivity and cultural awareness.

The problem begins with the recordings themselves. Many of the materials submitted to modern archives are in poor condition. The background noise from old microphones, distant echoes, overlapping voices, and dialectal variations makes it difficult to apply automated transcription solutions. Whisper-based systems, such as WhisperX, are powerful but can only reach their full potential when the audio has first been professionally cleaned and restored.

This restoration process is often underestimated. It includes frequency analysis, noise reduction, rebalancing speakers, and sometimes manual filtering of static artifacts. Only after this labor-intensive preparation can a machine begin to understand what was actually said. The quality of the restoration directly impacts the accuracy of the transcription—and by extension, the reliability of the preserved memory.

But transcription is more than a technical process. It is part of the ethical and cultural responsibility of anyone working in archives, education, or heritage preservation. When working with sensitive historical material, the question is not only how accurately something is transcribed, but how responsibly it is processed. Who gets access to it? Who decides what is translated and what remains in its original language? And above all: Is the transcribed text true to the spirit of the original voice?

Especially in a multilingual context, these questions become even more complex. Interviews from Africa, Latin America, Asia, or the Middle East often contain multiple languages, dialects, or regional codes that are not documented in traditional linguistic databases. Here, transcription is also translation—and this translation must avoid interpretative distortions. Otherwise, there is a risk that valuable knowledge will be standardized, distorted, or lost altogether.

Modern transcription systems that process files offline and locally, without sending data to cloud services, are particularly valuable for this. They guarantee data sovereignty, confidentiality, and full auditability—especially when the material is confidential, ethically sensitive, or politically charged. The system described here, for example, is not dependent on any cloud infrastructure. It runs entirely on local, high-performance GPUs and is therefore both fast and secure. Transcription takes place in multiple stages—restoration, segmentation, diarization (speaker separation), and interactive output—resulting in a polished document that can be easily archived or published.

In Part 2, we will explore how these steps work together and how new tools help not only preserve, but interpret, contextualize, and present audio recordings in a way that makes them accessible to wider audiences—while respecting the dignity of those who spoke.

Once a historical audio recording has been restored and technically prepared, the real work begins: interpreting, structuring, and presenting the spoken content in a way that does justice to both the speaker and the reader. Transcription in the cultural and historical context is not a mechanical act—it is a form of storytelling. And storytelling, in this case, demands not only accuracy but empathy.

The first step after audio restoration is segmentation—dividing the recording into meaningful units. This is not always based solely on speaker changes or pauses; it may involve thematic breaks, shifts in tone, or even emotional rhythm. A trained human ear often notices patterns that an algorithm misses. Thus, even the most advanced diarization systems (those that separate speakers automatically) benefit from manual review or correction.

Once the segments are defined, a second layer of decision-making follows: how do we format the content? Should we preserve every filler word, every repetition, every pause? Or should the transcript be “cleaned up” for better readability? This question alone touches on the core of cultural ethics. In some traditions, pauses, silence, or hesitation carry meaning. In others, verbal redundancy is a sign of respect or reflection. Transcribing is therefore not merely a technical service—it is an act of interpretation.

To respect that complexity, our system produces a dual-layer transcript: one version close to the original recording, and one edited for clarity and narrative flow. Both layers are kept separately available, so readers—and researchers—can decide which they want to engage with. This transparency is key to working responsibly with oral histories.

Next, we consider contextual metadata: Who is speaking? When and where was the recording made? What was the purpose of the conversation? These questions often have no obvious answers—especially if the original materials were poorly documented. Our process includes the option of embedding metadata directly into the transcript, so that each segment contains orientation points for further archival or research use.

Beyond metadata, we also generate chapter structures, optional summaries, and even visual content. These additions are not mere decorations; they help guide the reader through complex material. For example, an hour-long oral history interview might be broken into six thematic chapters: early life, education, conflict experience, migration, cultural practice, and final reflection. Each chapter begins with a brief summary and optional visual cue. In doing so, we make long-form oral content approachable, without distorting or fragmenting it.

An important aspect, often overlooked, is accessibility. Many audio recordings, especially those in indigenous or minoritized languages, are of limited use if only experts can understand them. That’s why we advocate for multi-language output where possible. For example, if an interview was conducted in Quechua and later translated into Spanish, both versions should appear in the transcript. This is not a “woke” luxury, but a simple matter of intellectual respect: the original speaker has the right to see their words reflected in their own language—and future generations benefit from this duality.

A striking example comes from South America, where several university-led initiatives now produce bi-lingual transcripts of interviews with indigenous elders. These transcripts are published not only for academic audiences but also for the communities themselves. The elders and their descendants can read, verify, and reinterpret the content—often finding pride, identity, and recognition in the process. The transcripts become not just historical documents, but living texts.

Of course, the tools behind this workflow are highly technical. But we are careful to present them not as black boxes, but as transparent, customizable instruments. We use only offline, secure, GPU-accelerated systems—meaning that all processing happens locally, without internet upload or dependence on external services. This allows maximum data security, even in politically sensitive projects.

In Part 3, we will explore how this approach bridges the gap between historical fidelity and modern relevance—how technology, ethics, and cultural sensitivity can converge into an end product that not only archives voices, but amplifies them for future generations.

The final stage in working with historical audio is not merely a matter of formatting or polishing a transcript—it is the stage where memory becomes testimony, and testimony becomes legacy. At this point, technology must step back and give space to something far more delicate: ethical responsibility.

Our transcription process does not end with text. It ends with a decision: What do we publish, and for whom? These are not neutral questions. They ask us to consider the relationship between the originator of the recording (the speaker), the interpreter (our team), and the recipient (the future reader, researcher, or archivist). Each of these stakeholders deserves to be seen.

This means that our archive-ready outputs are always adapted for the context in which they will be read or used. For scientific institutions, the structure may lean toward metadata richness and semantic tagging. For museums, it might include an aesthetic layer: curated visuals, commentary, or even cross-references to other cultural materials. And for communities—especially those whose histories have long been recorded by others—it means giving them tools to take back their voice.

Let’s take an example from indigenous knowledge systems. In recent years, the growing awareness of decolonial practices has led to the realization that oral histories must not only be recorded but also made accessible in a form the original communities can actually use. What good is a French-language transcript of a Wolof oral tradition if no one in the village speaks French?

That is why we encourage the use of bilingual transcripts or even multilingual presentation layers. These may include:

A section in the original language (e.g., Wolof),

A research-language version (e.g., French),

And a community-oriented summary or visual interpretation.

This triadic approach bridges the gap between academia, technology, and human context. It ensures that no voice is flattened or abstracted into the archive without care.

But it’s not just about language. Cultural precision also includes:

Preserving metaphorical speech,

Marking emotionally loaded sections with care,

Avoiding assumptions in translation,

And recognizing when silence speaks volumes.

This is especially important in cases where the recordings include trauma, ritual, or spiritual content. In some traditions, naming the dead or revealing certain practices in written form is taboo. Our team is trained to identify such elements and engage with the communities involved to decide on the appropriate treatment—sometimes that means redacting, sometimes embedding warnings, sometimes offering the content in sealed or restricted forms.

Here, human judgment outweighs automation. No large language model can yet decide whether a section of spiritual testimony should be public. That’s a conversation between human beings, with human empathy.

Furthermore, we maintain full traceability in our process. Every edit, decision, and tool involved is documented. This is essential for projects working under public funding, university cooperation, or cultural heritage grants. Our goal is not just a beautiful transcript, but an auditable process that meets the highest standards of research ethics and data stewardship.

In this way, transcription becomes not only an end product—but a platform for deeper engagement:

Researchers gain structured, multilingual data.

Communities regain agency over their narratives.

Archives receive transparent, high-quality content that is future-proof.

In the end, we must remember: voices are not data. They are traces of lives, emotions, struggles, wisdom. The role of modern transcription is not to sterilize or standardize them—but to make them resonate across time and space.

And this is why we do what we do. Because in every restored, transcribed, and structured voice, there is a human being who deserves to be heard—on their terms.

If your institution, archive, or initiative is working with complex, sensitive, or culturally significant audio material, we invite you to start a conversation with us. At R2 Mechanics, we don’t just transcribe—we listen, we restore, we structure, and we respect.

Whether you’re preparing a heritage project, curating an oral history archive, or navigating multilingual materials with cultural nuance, our offline, ethical, and high-fidelity workflow is designed to meet your needs—technically, emotionally, and historically.

Reach out to explore collaboration, request a sample, or discuss your archival goals. We look forward to helping you bring forgotten voices back into focus—with the dignity they deserve.